Home Mail Articles Supplements Subscriptions Radio

The following article first appeared in Left Business Observer #115, Mayt 2007. It retains its copyright and may not be reprinted or redistributed in any form - print, electronic, facsimile, anything - without the permission of LBO.

Private wads

Back in the 1980s, it was leveraged buyouts (LBOs, for which this publication was named, sorta). In the 1990s, it was the dot.com’s. And in this upcycle—do we ever have deep downcycles anymore?—it’s been private equity (PE). Sure, the hedge funds have been playing a major supporting role, but they’ve been around for a while. The stars—armed with an economic philosophy even—have been private equity. Sometimes it seems like the 1980s all over again.

Civilians who discard the business pages unread may have first made the acquaintance of PE with the news that Cerberus Capital would soon be taking Chrysler off Daimler’s hands. You can understand why Daimler would want to sell—to be liberated from the burden of a money-losing maker of Dodges to focus on the profitable business of making and selling Mercedes-Benzes. But what will Cerberus—a firm named for the multi-headed guard dog of Hades that specializes in buying up the near-dead—do with Chrysler? According to the PE playbook, slim it down, cut costs, and sell it a few years down the road. There may be no UAW left by the time they’re done with the company; GM and Ford will demand equal treatment.

Magic and gain

A few words about PE and its magic. Private equity funds consist of pools of capital raised from institutional investors like pension funds and very rich individuals, all gathered to do deals. The point of such deals is to take public firms private (public in the sense of being stockholder-owned, not forms of socialist enterprise), strip them down by cutting costs (laying off workers, shutting unprofitable divisions, etc.), and, eventually either take them public again by floating a new stock offering or selling it wholesale to another buyer. Such a sale will, if all goes well, yield far more in proceeds than the private equity firm spent buying up the target and fixing it. While waiting for the magic to kick in, the managers pay themselves large fees.

It’s all highly reminiscent of the LBO boom of the 1980s. Then, individual hotshots like Carl Icahn and buyout boutiques like Kohlberg Kravis Roberts (KKR)—back bigtime in recent years—borrowed billions to take over what they deemed to be underperforming firms, which they would fix up and then sell back to public stockholders. Initially rational on their own terms (though often brutal to workers), the deals got hugely bloated by the end of the decade. Any cost savings from hammering the workers was more than offset by huge debt service costs. Debt-heavy deals went out of fashion in the 1990s, and didn’t return to the scene in any size until a few years ago.

While the LBO mania was cooking, its theorists, notably Harvard’s Michael Jensen, proposed that the public company was obsolete, and the LBO form was its replacement. The logic was that high levels of debt would force managers to focus relentlessly on keeping costs down (all costs, that is, except interest on the massive loans that funded the deals). And the lack of public stockholders and pesky security analysts would free managers to focus on the long term instead of maximizing short-term profits. When the leveraging movement came crashing down in the early 1990s, all these nice theories were forgotten. Nearly two decades later, they’ve been reborn.

Blackstone

Though there are nearly 3,000 PE firms worldwide, several names dominate the scene. These are The Carlyle Group (famous for its associations with the national security state), KKR, Goldman Sachs’ in-house PE group, Blackstone, and Texas Pacific. (Cerberus is rather small as these things go.) Although U.S. firms dominate the PE racket, Asians and Europeans are catching up. Right now, the most interesting of the PE swarm is Blackstone, because it did the biggest deal in history—the $39 billion purchase of Equity Office Properties, the largest commercial landlord in the U.S.—and because it’s about to go public itself.

Blackstone was founded in 1985 by Peter Peterson and Stephen Schwarzman, who met when they were bankers at Lehman Brothers. Peterson, who was Nixon’s Commerce Secretary and became famous in the 1980s as a gloomster bent on Social Security privatization, is an octogenarian who’s on his way to going emeritus at Blackstone; Schwarzman is the public face of the firm.  They reportedly hate each other now—so much so, that Peterson didn’t even attend the party of the year, the $3 million 60th birthday fete that Schwarzman threw for himself and his 1,500 closest friends in February, which featured the 62-year-old Rod Stewart at the headline entertainer.

They reportedly hate each other now—so much so, that Peterson didn’t even attend the party of the year, the $3 million 60th birthday fete that Schwarzman threw for himself and his 1,500 closest friends in February, which featured the 62-year-old Rod Stewart at the headline entertainer.

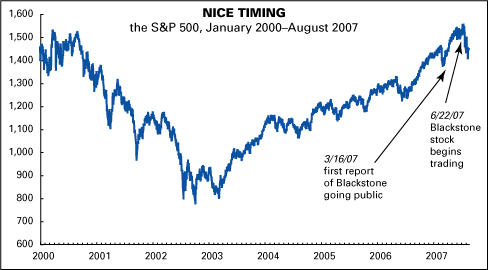

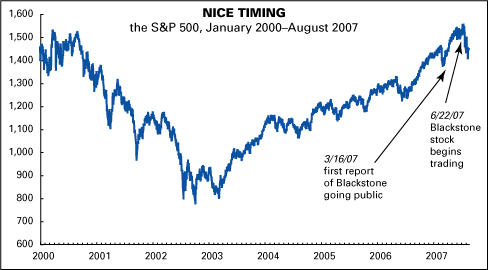

At a lavish party at the end of that decade, 1980s buyout star Saul Steinberg famously said to his wife, “Honey, if this moment were a stock, I’d short it” (i.e., bet on its decline). It’s not been reported whether Schwarzman said anything similar at his party. But in effect he’s doing something similar by taking his firm public—selling shares on terms favorable to himself and the 50-some senior execs who currently own and run the firm (see below for more). This is an interesting turn for Schwarzman, who not long ago pronounced the public securities markets “overrated.”

So now that he’s tapping those markets, it would be easy to lambaste Schwarzman as an opportunist and hypocrite—which he is, so let’s not pass up the lambasting opportunity. But this does bring up an interesting practico-theoretical issue for the prevailing ideology. The stock market is supposed to provide an instant real-time evaluation of a company’s management and prospects, and offer guidance on whether a new direction is in order. So how is it that PE can do better by taking firms out of view of the public markets? Either the markets are seriously flawed, or PE is selling us a bill of goods. If there are great gobs of value to be generated by taking public firms private, then how are the public markets allowing these opportunities to go unexploited?

Or maybe it’s all just cyclical. At the end of bear markets—the early 1980s, say, or the early 2000s—the markets are seriously undervalued, but most investors are too scared to notice that. So the LBO or PE guys can make the first moves. Then the broader public catches on, and the smart money decides it’s time to cash in. Maybe the public markets are overrated—for the public, that is.

Addendum: the Blackstone prospectus

You gotta love prospectuses. In a bullshit-saturated media culture, they’re full of harsh truths. Truths that few take seriously, though: when you’re buying securities, you just want to believe.

In that spirit, let’s dig into the prospectus for the Blackstone IPO. [Note: this article was based on a preliminary version of the prospectus; the link is to the final version, in which the blanks were filled in.] On the bright side, we learn that it’s been a rather successful enterprise. It comprises several lines of business, among them a private equity arm, a hedge fund that invests in other hedge funds, a real estate collection, a couple of mutual funds, and a fund that invests in “distressed securities” (stocks and bonds of troubled companies), which sum to $88 billion under management. The private equity fund, a $33 billion hoard established in 1987, has returned an average of 31% a year—23% after the partners took their cut, or nearly a third of the profits. (Several of the other funds have much less impressive returns, in the 8–12% range. But oh! the management fees!!)

While 23% is still a little over twice what the stock market returned over the period, Blackstone used a lot of borrowed money. If you’d borrowed half the money you had invested in the stock market, a legal and reasonably prudent thing to do, then your returns would be close to what Blackstone’s outside investors got. The real juice in this game is for the partners. Oh, and they’re going to take almost $4 billion of the IPO’s proceeds for themselves. They’ll also hold considerable blocks of the new Blackstone stock, but considering all they’ve taken out of the firm already, they’ll be sitting a lot prettier than the new public shareholders.

After going public, Blackstone will keep some cut of the profits—a presumably large cut, but there’s no number in the prospectus. Stockholders “will have only limited voting rights and will have no right to elect our general partner or its directors, which will be elected by our founders.”

Blackstone confesses to a long and scary set of risks: the financial markets could turn ugly; going public could drive away the talent responsible for all those years of splendid returns; lifting the veil of secrecy that comes with going public could ruin the magic; Congress or the regulators could come crashing down (e.g., they pay taxes on fee income at the favorable capital gains rate, which makes little sense to anyone not earning the fees); outside investors could demand their money back, which could leave Blackstone high and dry; losses could wipe the firm out completely and then some; shareholders have no recourse if the management team screws up; the inner circle has interests different from the shareholders, and reserves the right to think only of itself; an unspecified share of the proceeds of the stock offering will go into the pockets of the founders, and won’t be available for the business; shareholders could have to pay taxes on Blackstone’s income even though it didn’t distribute any of it as cash to shareholders.

The Chinese government is in for $3 billion. But they want to make friends in the U.S. and have another $1.2 trillion to spare. Why would anyone else want in?

[Click here for a Blackstone price history.]

Home Mail Articles Stats/current Supplements Subscriptions Radio

They reportedly hate each other now—so much so, that Peterson didn’t even attend the party of the year, the $3 million 60th birthday fete that Schwarzman threw for himself and his 1,500 closest friends in February, which featured the 62-year-old Rod Stewart at the headline entertainer.

They reportedly hate each other now—so much so, that Peterson didn’t even attend the party of the year, the $3 million 60th birthday fete that Schwarzman threw for himself and his 1,500 closest friends in February, which featured the 62-year-old Rod Stewart at the headline entertainer.