Home

Mail Articles

Stats/current

Supplements

Subscriptions

Links

The following article appeared in Left

Business Observer #91, August 1999. It retains its copyright and

may not be reprinted or redistributed in any form - print, electronic,

facsimile, anything - without the permission of LBO.

Last November, LBO reported

that a group of mostly-teenage McDonald's workers in Squamish,

British Columbia, had voted to join the Canadian Auto Workers, despite barely legal

union-busting tactics as recognizably McDonald's as the Golden

Arches. Throughout contract negotiations this year, McDonald's

lawyers have challenged the CAW on every legal technicality they

could invent -- including the legality of a strike vote and a

bizarre interpretation of Canadian child labor laws. Says CAW

organizer Roger Crowther, "They won nothing but that's not

the object of the game. The point is to wear down the union."

And wear it down they did. Having stalled negotiations for

months, McDonald's began a decertification campaign in June. On

July 2 -- by which point less than half of the original shop members

were still working there -- a majority of employees voted to disband

the union. It was the closest any Canadian McDonald's workers

have come to a collective agreement -- there have been a few attempts

in both Canada and the U.S., but they've all been squashed much

earlier in the process -- and, given the initial promise, it's

a dispiriting outcome.

In Squamish, McDonald's faced a rare set of adversaries: a

union local with a demonstrated gift for organizing the fast-food

sector, and the British Columbian labor code, which is union-friendly

even by Canadian standards. McDonald's relentless determination

and limitless resources were able to frustrate the organizers

even in that environment. But the ordeal in Squamish is only one

of many recent attempts to drag the burger giant to the bargaining

table -- some of which have taken place in startlingly unexpected

places.

Indonesia

In some of those places, resistance to unions takes harsher

forms than PR and litigation. According to Gerard Greenfield, an organizer with the Indonesian

branch of the Geneva-based International Union of Food, Agricultural,

Hotel, Restaurant, Catering, Tobacco and Allied Workers' Associations

(IUF), acts

of military violence and intimidation against Indonesian workers

occur almost every week. Even pamphlets on union organizing can

provoke military intervention. But against this horrific backdrop,

there has been some organizing activity among McDonald's workers.

In July 1998, 160 workers at Indonesia's largest McDonald's outlet,

in a shopping mall in Surabaya, East Java, held a two-day strike.

They were protesting their working conditions (among the worst

in the nation, according to Greenfield), their wages (below the

legal minimum, which is the U.S. equivalent of 57cents an hour),

and the planned layoff of sixty workers. In addition to written

employment contracts, a wage increase, and an end to arbitrary

dismissals, the Surabaya workers demanded the right to unionize.

On paper, Indonesian workers actually do have the right to

esablish unions; soon after coming to power, the Habibie government

ratified ILO Convention 98, which guarantees the right to collective

bargaining. But given the military's homicidal hostility to labor,

that doesn't mean much -- and, besides, since the U.S. has never

ratified that convention, American companies have little incentive

to comply with it. Also, the ILO in Jakarta is weak and corrupt.

As Greenfield points out, it fails to recognize many plant-level

unions that are not connected to a federation -- or to the horrible

government-sponsored union SPSI; ILO officials probably would

have seen the Surabaya union as illegitimate because it wasn't

registered with the Labour Department.

On the second day of the Surabaya strike, workers declared

a union and elected leaders. But management refused to negotiate,

harassing employees and threatening to fire them for joining the

union. When support for the union deteriorated, all of its elected

leaders were fired. More than 50 workers quit the restaurant in

protest, but those who stayed on were forced to sign letters agreeing

not to hold any more demonstrations or to attempt to form a union.

In August, the IUF, which has helped to coordinate McDonald's

unionization efforts in numerous countries, plans to launch a

national campaign informing workers about the illegality of such

agreements, which are common among U.S.-based fast-food companies

in Indonesia like A&W, Wendy's, Dunkin Donuts and KFC. Despite

the toothlessness of the ILO Conventions, Greenfield believes

they can be used to raise workers' awareness about their rights.

To avoid military interference, IUF organizers plan to avoid demonstrations

or pamphleting. They'll meet with workers in small study groups,

working closely with labor organizations all over the country,

as well as the fired union leaders in Surabaya, who now run a

small street food stall. "McDonald's continues to expand

even while other fast-food restaurants are shutting down,"

says Greeenfield, "and it's a growing workforce of young

workers in Indonesia, like in most countries, so we have to get

them organized."

As Lenin said...

Efforts in Russia have been even more serious. Communist worship

of the Golden Arches has long been a stimulus to

Western joy, so when workers in a McDonald's' factory just outside

Moscow joined the Russian Commerce and Catering Workers' Union

last November, it wasn't just a marker of economic desperation,

but also quite the semiotic fuck-you. Since the ruble's disastrous

plunge the previous August, McDonald's had been laying off workers

and letting their  real wages devalue

by more than half (before the crisis, the average wage was roughly

$200 a month). Post-devaluation, most of the plant's employees

would have to work for two hours to earn enough to buy a Big Mac,

which in Moscow costs about $1.46, compared with an hour before

the ruble's collapse. As Natalia Gracheva, a systems controller

who had been working for McDonald's for nine years, told Toronto's

Globe and Mail, it was a "revolutionary situation.

As Lenin said, the smell of revolution was in

the air."

real wages devalue

by more than half (before the crisis, the average wage was roughly

$200 a month). Post-devaluation, most of the plant's employees

would have to work for two hours to earn enough to buy a Big Mac,

which in Moscow costs about $1.46, compared with an hour before

the ruble's collapse. As Natalia Gracheva, a systems controller

who had been working for McDonald's for nine years, told Toronto's

Globe and Mail, it was a "revolutionary situation.

As Lenin said, the smell of revolution was in

the air."

About half of the plant's 400 workers signed union cards; under

Russian labor law, a company has to recognize a union even if

only three people sign up. McDonald's harassed the pro-union employees

mercilessly: cutting off their work phones so they couldn't talk

to each other, depriving them of bonuses routinely granted to

other workers, and punishing them for the smallest infractions

(one worker was disciplined for returning from a bathroom break

one minute late). Gracheva, the union leader, was denied part

of her salary. While Russia's climate does make it difficult to

fire workers simply for union membership, the company has been

quick to find other reasons to fire union leaders; one union member,

fired for being a drunk, a charge he denies, is suing the company

for illegal dismissal. In January, the Moscow city government ordered McDonald's

to recognize the union.

"After that, they formally recognized the union, but not

in practice," Kirill Buketov, coordinator of the Moscow branch

of the IUF, who has been helping the McDonald's workers, told

LBO. "They're still

hassling the workers." McDonald's has barred union members

from talking to each other during the workday, and cut union members'

work week in half (down to twenty hours). In February, the union

members submitted a contract to McDonald's, but the company never

responded. In May, the city intervened again, ordering McDonald's

to negotiate a collective agreement with the union, but so far

the company hasn't budged. Barely a dozen of the original pro-union

employees remain at the plant. Says Buketov, "This is against

all the laws. As long as union members aren't trying to throw

a bomb, no one has the right to obstruct its actions." But

labor laws in Russia, as in Indonesia, aren't enforced. Russia's

unions are even weaker than its government, and public opinion

is practically irrelevant in a country where most people can't

afford fries.

Euroburgers

McDonald's unions fare better in regions with fewer poor people.

In regions populated by desperately impoverished potential workers

(like Russia, Indonesia, and parts of the United States) replacing

agitators is no problem, as Katherine S. Newman observes in No

Shame in My Game, her study of burger flippers in Harlem.

It doesn't take very long to train people, so continuously replacing

agitators is always cheaper than negotiating with a union.

In Europe, things aren't quite as dismal. In

Sweden, Denmark, Norway and Iceland, all McDonald's employees

work under a collective agreement, as do considerable numbers

in Germany, France, Finland, Ireland, The Netherlands, and Austria.

In Belgium, the United Kingdom, Spain, and Italy a handful (1%

or less) of McDonald's workers are unionized, estimates the IUF's

Patrick Dalban-Moreynas. With few exceptions, union victories

over McDonald's have been won by well-coordinated strikes and

boycotts, militant protests, lengthy legal battles or extensive

worker education campaigns.

Some of the strongest current campaigns are national in scope.

Last fall in Germany, where about 4% of McDonald's employees belong

to a union, members of the Food and Allied Workers' Union (NGG)

staged protests in over fifty cities, for a week. The actions

were part of a campaign to publicize McDonald's' systematic harassment

of its union shop, or "works council" members, as well

as the company's more creative union-busting tactics. (Pro-union

workers in Germany are frequently bribed to quit their jobs, sometimes

to the tune of 100,000 DM, or $65,000.) The union has been staging

these annual actions since 1996, and each year the protests swell

its ranks slightly; this year's is being held as this issue of

LBO goes to press.

|

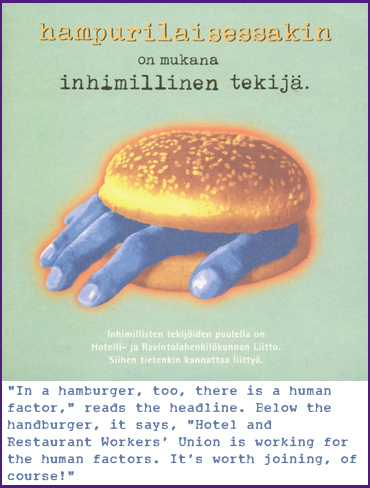

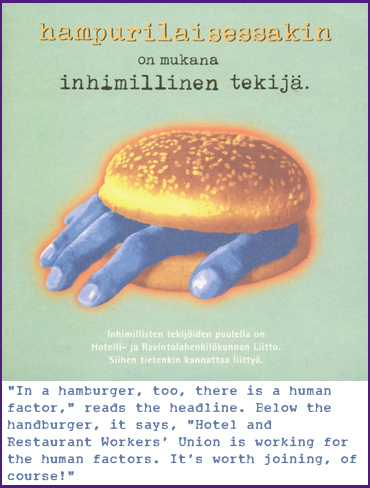

| The cover of a recruiting

pamphlet from the Finnish Hotel and Restaurant Workers' Union.

To contact them, write PL 327, 00530 Helsinki, or call +358-9-77-561,

or fax +358-9-7756-223 - or email them by clicking here. |

In Finland, the whole restaurant sector (including non-unionized

workers) works under a collective agreement, but a decade ago,

the union (Hotel

and Restaurant Workers' Union) had to organize a national

boycott of McDonald's to get the chain to comply. Since then,

the union has continued to recruit McDonald's workers, and now

about 6% of Finnish McDonald's employees are union members. [One

of their recruiting pamphlets is reproduced nearby.] The union

recently negotiated a startling concession from McDonald's; two

shop stewards (one representing Helsinki, another the rest of

the country) would be allowed to work on union business on McDonald's

time.

Many unions avoid McDonald's, or are quickly discouraged by

it, because, as Dalban-Moreynas of the IUF says, "They get

little return on their investment. [Organizing McDonald's] is

very time and money-intensive, and many just decide it's not worth

it."

Beyond legalism

There's no doubt that McDonald's is an implacably antiunion company, and responds to eruptions

of union fever in consistent ways. But since unionizing efforts

clearly fare better in some countries than others, it's reasonable

to ask what makes the difference.

Dalban-Moreynas says there is no single explanation. Better

labor laws and enforcement mechanisms do help: most of the countries

where McDonald's organizing has succeeded have friendlier labor

laws than the United States -- less time for elections, stricter

rein on employers' union-busting tactics, etc. But labor codes

don't explain everything: even where the laws favor labor, as

in British Columbia, McDonald's has enough money to litigate unions

to death. And McDonald's has no qualms about breaking laws, as

the Indonesian and Russian experiences amply demonstrate.

Also, some of the most devastating union-busting strategies

are hard to prove; firing pro-union workers is a good example.

Even in the U.S., the law frowns upon this practice, but it happens

so often that in a 1994 Commerce Department study, three-fourths

of nonunion workers said that if you seek union representation,

you're likely to lose your job. They're not wrong; according to

analyses of NLRB data by Cornell researcher Kate Bronfenbrenner, a third of companies

have illegally fired union supporters during elections. An employer

can easily find reasons to fire people who are poor, lacking education,

and young, as the McDonald's workforce tends to be; things that

used to be tolerated, like lateness, can suddenly become grounds

for dismissal in a union drive. And many young workers don't even

realize that firing people for union activity is illegal.

A further measure of the limits of legalistic explanations

is the experience of Nordic countries, all of which have essentially

the same labor laws, according to Dalban-Moreynas. But Swedish

unions have always had a harmonious relationship with McDonald's,

while Norwegian and Danish unions have had to strike and boycott

to get the company to honor legally-mandated union rights. Of

the three countries, Dalban-Moreynas says, Sweden has the stronger

national labor movement; it may be that movements equipped for

serious and coordinated campaigns are even more important than

laws. Of course, comparing Norway and Denmark to the United States

makes the case for a strong overall labor movement even more dramatically;

it's difficult to imagine U.S. unions organizing strikes and boycotts

that could pinch hard enough to make a fast-food leviathan say

uncle.

Meanwhile, back in Squamish, the CAW's Roger Crowther says,

McDonald's has convinced most employees that they don't need a

union anymore. Conditions have improved cosmetically; the company

has replaced an unpopular manager with someone the workers like

better, and employees are getting more hours. "They throw

them the odd party here and there," Crowther says darkly.

"So happiness has returned to the Golden Arches at Squamish."

Home Mail

Articles

Stats/current

Supplements

Subscriptions

Links

real wages devalue

by more than half (before the crisis, the average wage was roughly

$200 a month). Post-devaluation, most of the plant's employees

would have to work for two hours to earn enough to buy a Big Mac,

which in Moscow costs about $1.46, compared with an hour before

the ruble's collapse. As Natalia Gracheva, a systems controller

who had been working for McDonald's for nine years, told Toronto's

Globe and Mail, it was a "revolutionary situation.

As Lenin said, the smell of revolution was in

the air."

real wages devalue

by more than half (before the crisis, the average wage was roughly

$200 a month). Post-devaluation, most of the plant's employees

would have to work for two hours to earn enough to buy a Big Mac,

which in Moscow costs about $1.46, compared with an hour before

the ruble's collapse. As Natalia Gracheva, a systems controller

who had been working for McDonald's for nine years, told Toronto's

Globe and Mail, it was a "revolutionary situation.

As Lenin said, the smell of revolution was in

the air."